Amanda Kachadoorian: Botanical Hybridity OF San Diego’s Multicultural History

february 20–July 3, 2021

“To be placed in a new environment is a way to understand the internal and external aspects of life. I express the notions of identity, culture, ephemerality, and nature in my work. Every concept has an underlying relationship with one another which is a constant process and investigation. Through the experimentation of mixing various plant life representative of individuals and/or locations multi-cultural background, I aim to create the notion of hybridity from a post-colonial identity. While creating an atmosphere of identity through nature, I use a personal motif, “heart in a bowl” which symbolizes the effects of displacement, isolation, and anxiety. In conclusion, I create a dynamic atmosphere while providing dialogue surrounding perspectives of individuals and our society.”

—Amanda Kachadoorian

Learn more about the artwork in this exhibition:

Central San Diego, 2020. Oil on canvas, 120" x 36" (2 panels, each 60" x 36"). From the City of San Diego Civic Art Collection.

Central San Diego, the newest panoramic landscape painting in this series, places viewers on the northwest side of Coronado island looking westward to the ocean under a stormy sky. Point Loma is shown in the background as it’s earliest inhabitants knew it, covered in local oak and pine trees. Moving across the San Diego Bay, the work’s botanical subjects stand in two groups in the foreground. Kachadoorian has combined this collection of flora and fauna to tell the stories of the city’s inhabitants, how they came to be here, and how different groups have used the land in this slice of San Diego throughout history.

Kachadoorian’s layers of meaning extend beyond the hybridized plants–the stormy sky overhead is a reference to Mike Davis’ 2005 book, Under a Perfect Sun: The San Diego Tourists Never See that exposed uncomfortable truths behind the public persona of this carefree vacation destination. Almost 16 years after its publishing, these issues persist. In a post of the work during the summer of 2020 amid calls for justice by the Movement for Black Lives, the artist wrote, “This painting represents all the cultures that have contributed to the history and community of San Diego...From the Kumeyaay tribe that inhabited this land for thousands of years to the various cultures that have migrated from various countries for the “American Dream” in hopes for a better future, EVERYONE has contributed to the development of this city and deserves the same respect and opportunity EQUALLY, REGARDLESS of ethnicity, race, gender, sexual orientation, age, and economic income.”[27]

Her trademark floating heart is tucked in amongst the plants protected by a red-tinted glass bowl. The heart is a tender, vulnerable thing. One can easily imagine the caution and vigilance necessary to transport it over a long journey to a new home or protect it from centuries of settler colonialism. This painting is a representation of collective humanity and reminds viewers to see this work, and their neighbors, through a lens of compassion even while interrogating legacies of discrimination and violence.

Akiko Suari

[27] https://www.instagram.com/p/CCHqWFzjPjE/?hl=en

South Bay, San Diego, 2019. Oil on canvas, 120" x 36" (2 panels, each 60" x 36"). From the collection of Zoe Kleinbub.

The panoramic canvas South Bay, San Diego stretches from daybreak over the Jamul mountains in the east to the sun sinking into the Pacific Ocean in the far west. Viewers are placed into a rolling landscape of golden grass that runs uninterrupted to what locals will recognize as the Sweetwater reservoir, the building of which marked a boon in development for the South Bay. In 1886, Frank Kimball proposed the building of a dam that would allow the Sweetwater river to serve the growing population of National City.[1] Before this structure, the area bounced between years of drought and devastating floods. A consistent water source allowed agriculture and industry to expand bringing new people to the region. Aside from the reservoir, the landscape looks vacant, bringing to mind American photography and painting of the 19th century during westward expansion. However in reality, this landscape is populated by plants.

Akiko Suari

[1] Zaragoza, Barbara. “Sweetwater Reservoir.” South Bay Compass. Accessed December 18, 2019. http://southbaycompass.com/sweetwater-reservoir/.

National City, San Diego, 2020. Oil on canvas, 35" x 40".

The first painting in the South Bay sub-painting collection is National City, San Diego. National City is shown in the light of an early morning sunrise with east facing botanicals in front of a view towards an undeveloped and idealized landscape of National City and San Diego Bay.

The area represented in the painting became a development of railway systems and depots that shaped the land and culture of the South Bay in the late 19th century. In 1849 gold was discovered in California, which brought many people from all over the world seeking fortune to escape poverty. [3] Those who migrated to San Diego were mainly Chinese, Japanese and European settlers who worked alongside Indigenous people and Californians. In 1881, The Santa Fe railway system built a railyard in National City and in 1885, Southern California was connected with Santa Fe Railway to Barstow leading to an increase in population in San Diego and the South Bay. [3]

Before and after the first World War there had been an influx of migrants from the Philippines to San Diego. The majority of them were Filipino men who enlisted in the United States Navy in order to send money back to their families. Others worked on farms for low wages and endured suffering conditions. [5] As the Filipino community grew, so did the intermarriage of Mexican and Filipino people in the South Bay, which created an identity referred to as Mexipino. [6] Currently, there is a large Filipino and Hispanic community in National City along with other Asian cultures such as Vietnamese, Taiwanese, Japanese, and Chinese.

Amanda Kachadoorian

[1] Michael Wilken-Robertson. Kumeyaay Ethnobotany: Shared Heritage of the Californias. Published October 15, 2017.

[2] “Summary of shaw’s agave and its traditional use”. Summary of shaw’s agave and its traditional use - Department of Biology - College of Arts and Sciences - University of San Diego. University of San Diego Department of Biology. Accessed September 3, 2020.

[3] South Bay Historical Society Bulletin. Issue No. 4. Accessed September 4, 2020.

[4] Timeline of San Diego History: 1800-1879. San Diego History Center: San Diego, CA. Accessed September 4, 2020.

[5] Castillo, Adelaida M. “Filipino Migrants In San Diego 1900-1946 - San Diego History Center: San Diego, CA: Our City, Our Story.” San Diego History Center | San Diego, CA | Our City, Our Story. The Journal of San Diego History, 1976.

[6] Zaragoza, Barbara. Fronterizos: A History of the Spanish-speaking People of the South Bay, San Diego. Published January 3, 2018.

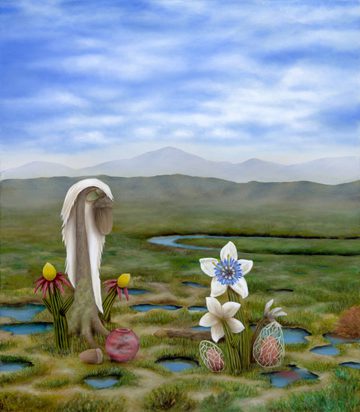

Sweetwater Marsh, San Diego, 2020. Oil on canvas, 35" x 40".

The second painting completed in the South Bay sub-painting collection, Sweetwater Marsh, San Diego depicts various hybrid plant species in the wet marsh lands of Sweetwater Marsh and its pools of water surrounded by vibrant green vegetation while looking out towards the San Miguel Mountains.

The Chula Vista Bayfront, where Sweetwater Marsh is located, has gone through many periods of development, including agricultural expansion, factory increases in World War ll, the construction of the Interstate-5 freeway, and the addition of Sweetwater Channel.

Factories made a particularly large impact. In the refuge of Sweetwater Marsh, a World War l processing plant called Gunpowder Point produced potash for smokeless gunpowder used by the British Army. [1] When the U.S entered into World War ll after the tragedy at Pearl Harbor, a demand was created for weapons and military planes. Fred Rohr, owner of Rohr Aircraft Company, bought ten acres of land on Chula Vista’s bayfront in order to produce 60,000 military planes.[3] As the demand grew, so did the company’s need for more industrial space that was developed along the Chula Vista bay front. This caused the growth of Chula Vista’s population, increasing from roughly 4,000 in 1940 to almost 30,000 in 1955. [3]

As the agriculture boom slowed in the South Bay in 19??, the landscape that we see today started to form with the construction of the Interstate 5 and 805 freeways. This development disrupted the landscape of the South Bay in many ways by forcing families and communities, mainly of Spanish speaking decent, to relocate, creating an unofficial division between Chula Vista, National City, and San Ysidro. [5] Today, parts of Sweetwater Marsh and Sweetwater Channel can be seen when driving down Interstate-5 South.

Amanda Kachadoorian

[1] U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, San Diego Bay National Wildlife Refuge | California - Sweetwater Marsh Unit. https://www.fws.gov/refuge/San_Diego_Bay/wildlife_and_habitat/Sweetwater_Marsh_Unit.html

[2] San Diego Bay National Wildlife Refuge - Wikipedia. Edited on 7 January 2020

San Diego Bay National Wildlife Refuge - Wikipedia

San Diego Bay National Wildlife Refuge is an urban refuge located on San Diego Bay in San Diego County, California. It is part of the San Diego National Wildlife Refuge Complex. It was dedicated in June 1999.

[3] “They made Chula Vista History” Booklet- Fred Rohr: An Aircraft, Pioneer- https://www.chulavistaca.gov/home/showdocument?id=7573

[4] City of Chula Vista – History – The Orchard Period https://www.chulavistaca.gov/residents/about-chula-vista/history

[5] Zaragoza, Barbara. Fronterizos: A History of the Spanish-speaking People of the South Bay, San Diego. Published January 3, 2018.

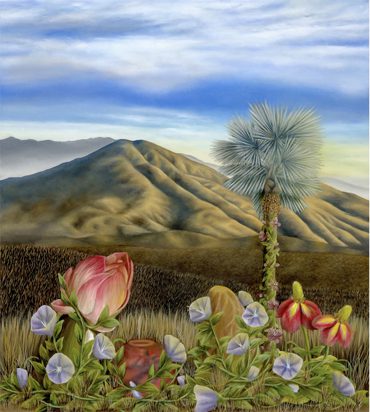

Spring Valley, San Diego, 2020. Oil on canvas, 35" x 40".

The final painting in the South Bay sub-painting collection is Spring Valley, San Diego depicts a scene lit by the sun setting in the west, shining along San Miguel mountains and the open plain, with botanicals in the forefront.

The San Miguel Mountains are a symbolic landmark in the South Bay that can be recognized throughout the region and a prominent backdrop for the community. Nearby is a natural spring that was used by the Kumeyaay tribe as a natural resource until the Spaniards forced them out to use the land for cattle farming. Spring Valley was named after this natural spring.[1] The majority of Spring Valley’s land had been used for ranches and agriculture. Also located in Spring Valley is the Sweetwater Dam, which was a major factor in the growth and development of the area. Before the construction of the dam it was difficult for farmers to produce consistent crop output due to devasting floods from the rivers in the winter and extreme droughts in the summer. Luckily, Sweetwater River, along with San Diego River and San Luis Rey River, were the very few locations that the streams did not subside year around. However as the population grew in San Diego, the rivers were not able to provide the necessary resources to sustain the region.[3] The need for the Sweetwater Dam was addressed by Frank Kimbell in 1886. [4] The many migrants present in California at that time due to the Gold Rush provided labor in the construction of the dam. Unfortunately, in 1916 the Sweetwater Dam collapsed and caused devastating flooding in the South Bay, often referred to as the The Great Flood of 1916.

Currently, the area surrounding Spring Valley and Sweeter Reservoir is part of suburban housing and has few markings of the large agriculture and ranches that were once prominent. However, the natural environment surrounding San Miguel is still intact with housing built alongside it.

*While Spring Valley is considered part of East County San Diego, it neighbors La Presa, which is informally part of Spring Valley and considered part of the South Bay as it is so close to the San Miguel Mountains.

Amanda Kachadoorian

[1] Spring Valley, San Diego County, California - Wikipedia. 15 September 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spring_Valley,_San_Diego_County,_California

[2] Spring Valley: Large unincorporated area got its start with home built from shipwreck wood – San Diego Union Tribune, Martina Schimitschek, June 30, 2019, https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/almanac/east-county/spring-valley/sd-me-almanac-springvalley-20170423-story.htm

[3] Sweetwater Dam – Wikipedia -https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sweetwater_Dam/ Information sources by Pourade, Richard F. “Chapter 3: Water Is King”. The History of San Diego. San Diego History Center.

[4] Zaragoza, Barbara. “Sweetwater Reservoir.” South Bay Compass. Accessed December 18, 2019. http://southbaycompass.com/sweetwater-reservoir/.

LEARN MORE

PROGRAMMING RELATED TO THIS EXHIBITION

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=43Ddp2IqyaE[/embedyt]Watch a clip from the Virtual Exhibition Celebration, live streamed on Thursday, March 25, 2021.

This program was produced in partnership with KOCT Television, The Voice of North County.

Header artwork: Southbay San Diego by Amanda Kachadoorian, from the collection of Zoe Kleinbub

If you would like to learn more about the artwork, including if the artist has work available to purchase, please email exhibitions@oma-online.org.